Sputter Box’s debut album, Sputter (SHRINKS THE) Box, features more than 25 brand new miniatures, each scored for bass clarinet, voice, and djembe.

“A Divine Image” is Track 13 on the album.

“. . . The simplicity of the language that gets the point across is something that really appeals to me. It’s still extremely powerful, and it’s not hidden in tons of layers of prose. I find that really refreshing, even though this poem is centuries old.”

NATASHA NELSON: Would you talk a bit about your inspiration for “A Divine Image,” whether you’ve worked with Sputter Box before, and anything you’d like to share about the score, to start?

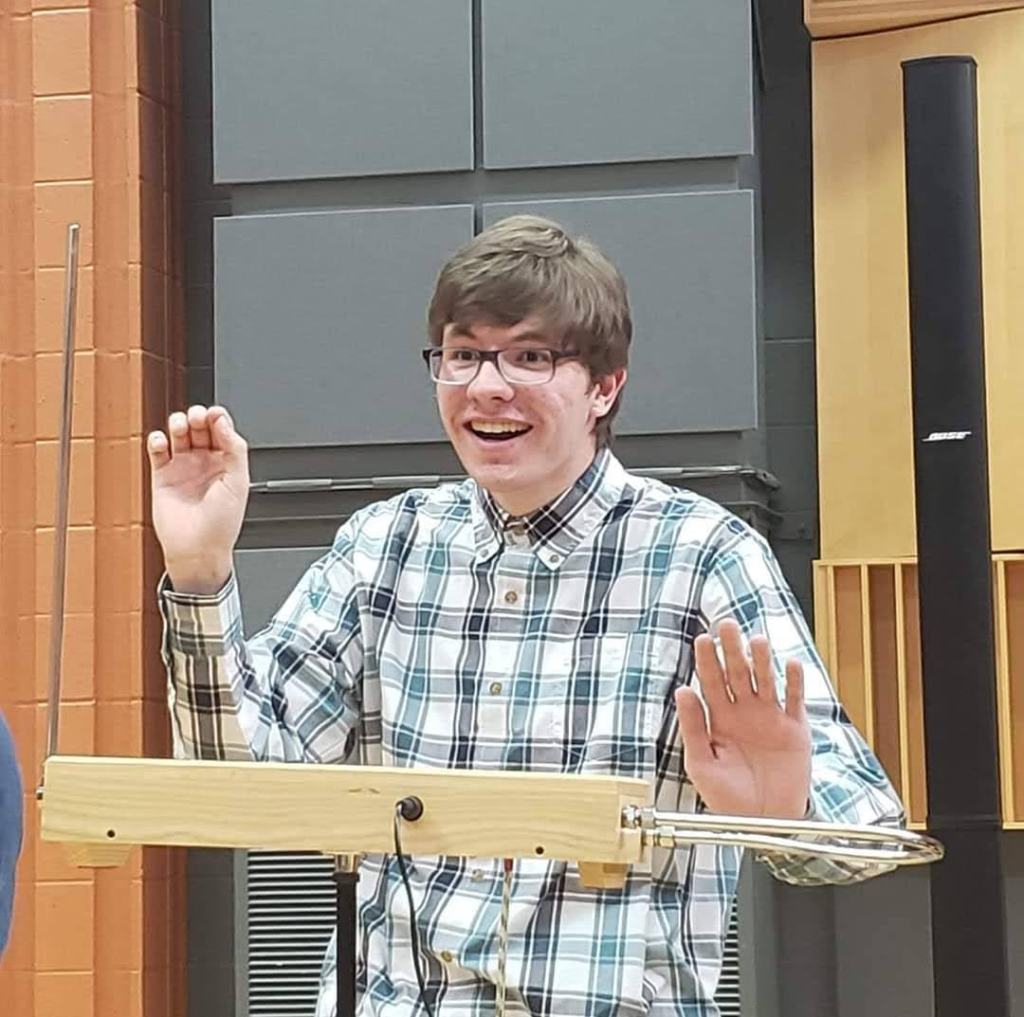

MARIO GODOY: Sure! So I had never worked with Sputter Box before, but I’ve been following them on social media via a few channels. I saw that they put out this particular call for composers to contribute a miniature, and it seemed like something I might be able to do pretty easily and quickly. It turned into something a little more challenging than I originally thought, but it was still a lot of fun to put together.

It was during the beginning portion of our quarantine period – our shelter-in-place period – and I was feeling kind of down creatively; I didn’t have anything to output at the moment. The world had just shut down. And then, when I saw this – that they still wanted to produce new music – I was really excited about it.

I decided to try to find inspiration from a text, rather than just trying to create some music. I did some digging around on the internet for something short that spoke to me, and I knew that I would only have a minute, right? A minute to get a message across.

I went through all the A’s, and then I got to the B’s: I got to William Blake and started looking at some of his poems. A lot of them are very, very long, but I found a couple short ones. This one stuck out to me. I put it aside and kept going through poets and poets . . . and I kept coming back to this one because it seemed like such a perfect, poignant piece. I thought that I could maybe make something really interesting from it.

Have you written for voice and set text previously?

MG: I’ve done it before. I’ve written a couple of various art song cycles and I’ve written for chorus. It’s not something that I do too often—it’s definitely something I want to do more of because I really enjoy doing it. It’s the only kind of music that I write that I feel kind of almost writes itself, in a way, just because I’m so used to speaking and singing. I know how the human voice and how diction works, so vocal music comes very easily-ish. It’s something that I’d really love to explore more.

And have you written for this trio’s instrumentation before?

MG: No. That’s one of the other things that I was really interested in: the fact that this instrumentation is so unique. I’ve written for voice, I’ve written for bass clarinet, I’ve written percussion music, but I’d never written for djembe.

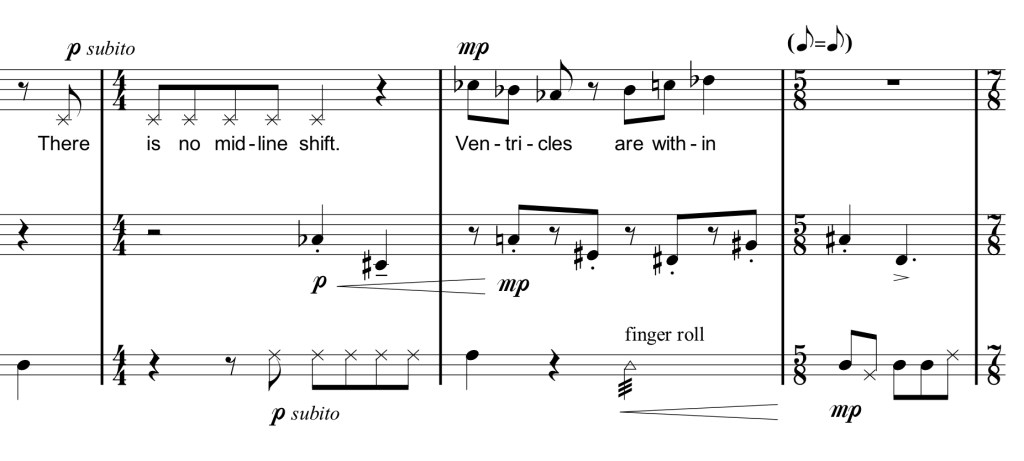

One of the things that Sputter Box sent along were [suggested] techniques, but they didn’t [request a] preferred notation. I tried looking up djembe notation, and there is a very specific notation that is not Western at all.

That would be so interesting to study!

MG: Yeah—it was really interesting to look at that and then see how people were interpreting it in Western notation. I decided to keep my notation very, very simple: a regular notehead is just a regular hit, an x is a muted hit, and then an accent is a slapped hit. I kept it pretty simple because the majority of the piece is not as simple, so I wanted to make sure that it was as clear as possible, without making it overly complex with notation.

I’m looking at your score here and your notation for djembe. Would you describe the original notation for djembe that you researched?

MG: [There are] various letters that indicate the portion of your palm that you hit or the portion of the drum that you hit. It’s laid out rhythmically just like Western notation is, as well, but it’s less about pitch, per se, and more about the specific kind of hit.

Did the fact that you were writing “A Divine Image” specifically for a recording, at least in its premiere, affect your approach to composing this piece versus other pieces you write?

MG: Yes. Well, not necessarily versus other pieces I write—I write a lot for pieces that have a lot of disparate parts that lock together to form a big texture. This piece is basically that, still, but those locking parts are the djembe part and the bass clarinet part, working simultaneously on two seemingly different things to create one texture. That’s a big thing I like to do in my music.

I created that underlying rhythmic texture, and then I placed the vocal line on top of it in long and juxtaposed rhythms. The bass clarinet and the djembe are on this constant eighth-note grid, and the soprano is floating on top—there are some syncopated pieces, but there are also triplets that kind of float over the top of this driving rhythm. It’s two things, coexisting.

“That’s what I wanted to bring into this piece: that there’s this rigidity—this constant drive from the djembe and the bass clarinet. Then there’s the human aspect – the voice – which is the most human thing, that’s coexisting with this rigidity underneath it.”

Would you like to talk, even furthermore, about how the text is portrayed in that texture, or any other musical elements you’ve mentioned?

MG: There are two elements to the text that really spoke to me: there’s the human aspect, and then the underlying tension and disassociation, in a way, because it has to do with the fact that these negative emotions or reactions – or what we would see as negative – don’t exist outside the human condition. They’re not tangible. We, as humans, are making these things and are willing them into existence. And, that the human heart, and the mind, and the way we interact is not necessarily loving and peaceful, and not everything is soft. Human interaction is more rigid and set.

That’s what I wanted to bring into this piece: that there’s this rigidity—this constant drive from the djembe and the bass clarinet. Then there’s the human aspect – the voice – which is the most human thing, that’s coexisting with this rigidity underneath it. So I did want to play with that juxtaposition of textures to make them really feel different—but they also fit together. So it was the fact that it’s all part of the same thing, it’s all part of the human condition—that’s the way I tried to approach it. Hopefully it came across.

And is there anything in particular about how this poem is written that really struck you when you first came across it?

MG: I think a lot of it is the simplicity of the language. It’s very straightforward and to the point—it gets the point across quickly and powerfully. It’s just saying, “Cruelty has a Human Heart.” Humans are cruel individuals; cruelty doesn’t exist [outside them]. It’s something that we had to give a name to because of the human nature of it.

That simplicity of the language that gets the point across immediately is something that I really enjoy in poetry. So [with] some of the other poems that I’ve set – I’ve done a Walt Whitman poem for chorus – again, it’s that the simplicity of the language that gets the point across is something that really appeals to me. It’s still extremely powerful, and it’s not hidden in tons of layers of prose. I find that really refreshing, even though this poem is centuries old.

Was any part of the compositional process for this score challenging or surprising?

MG: I think the hardest thing was figuring out the prosody of the text because it’s so unmetered. It’s very straightforward text and I wanted that rhythmic element to the bass clarinet and the djembe. The hardest part for me wasn’t necessarily writing the bass clarinet part or the djembe part, but figuring out how I wanted the voice to sit with those parts.

And it’s a very deep – as in low – piece for the most part. Even the soprano part doesn’t go extremely high—it doesn’t go into the money notes, per se, in the soprano range. The highest note is an F[5], which is not that high for most singers. But it does go pretty low—it goes [down] to a low A at the end.

I noticed that, as well, about the tessitura.

MG: I figured if it can [be approached] in this downward motion, even if it’s kind of guttural, it would still have the effect that I wanted right there. But it sits in a very easy range. The hardest part of this is obviously the counting. I knew that that was going to be the hardest part, so I sent a click track as a reference track so they could all be completely synched up.

And this piece actually is exactly—I think it was 59.7 seconds long [laughs]. And I actually had to whittle it down by [about] half a second in order to get it into that timeline. I think I had to eliminate an eighth note somewhere.

Oh, interesting! I could imagine that even though that’s a very short duration to eliminate, that could be a challenging decision.

MG: Yeah, it was challenging. I was trying to figure out where I could trim one eighth note.

Did that eighth note end up coming from a cadential area?

MG: I think it came from somewhere in the opening introduction. [The meter] goes from 3/4 meter to 5/8 – to 7/8 – to 3/4 . . . so it may have been 3/4 – 5/8 – 4/4 – 3/4, or something like that at some point. I don’t remember anymore, because I really have internalized the flow of this piece [as it is now].

That sounds ideal! How does one – or how do you personally, rather – measure the quantity or length of material in a score when writing a piece with a specified duration? Is that something that comes innately through experience composing?

MG: I like those kinds of constraints. It’s harder to just have a blank canvas and someone says “go.” So to say you have to get your whole point across in one minute, I actually found extremely refreshing and it gave me my whole road map: I have my intro, I have my two stanzas, essentially. I can separate the piece into those two sections with a little interlude in between.

My road map was laid out for me before I even started writing any notes. I look for those kinds of constraints and I often have to set them myself when I’m writing my own music, which is sometimes trickier to do than I want it to be. I do like painting with limited colors and I think that time actually is a color in music, for sure.

That’s a really poignant and interesting observation, and I’ve never really thought of it that way. I think of timbres in that kind of vein, but that certainly makes a lot of sense.

MG: Yes, you perceive timbres differently in a short period versus over an extended period.

That’s very interesting! What do you think it is about the window of time it fits in that changes how you perceive a given timbre?

MG: That’s a good question. I think that it’s – at least for this particular piece – the fact that there’s only a minute of music, but you’re hearing basically a cacophony of sound. It forces you to listen a little bit more. It’s harder to just zone and let the music envelope you, which is really easy to do with longer pieces of music. You just sit back, and with this one, you’re kind of forced to listen to how the instruments are interacting the whole time. I like that. Actually, I really like both things. So, I approach my music in that way.

For my longer pieces, you should be able to just kind of let the texture wash over you, or you can really hone into what’s happening and how the voices are interacting. I’ve compared it to an abstract painting in a way, where you can stand back and look at everything, and see how everything is forming one big picture—you just kind of observe it. Or, you can get close and look at how every individual element is interacting with one another.

That makes a lot of sense, and it’s interesting to think of paintings versus music because of how they exist in time, as you’re describing. They have those different layers to them, there to experience in different ways, given their different materials.

MG: Exactly.

The above interview took place in June 2020. For more music by Mario Godoy, visit mariogodoy.com.

This article is part of a series, featuring interviews with 16 composers whose work is featured on Sputter Box’s debut album. Read the feature article here!

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity. #ShelterInSound