Sputter Box’s debut album, Sputter (SHRINKS THE) Box, features more than 25 brand new miniatures, each scored for bass clarinet, voice, and djembe.

“La Dame” is Track 04 on the album.

A second miniature by the composer, entitled “Trapped,” is Track 14.

NATASHA NELSON: I enjoyed reading the program note in the preface to the score for “La Dame”! Would you begin by sharing a few details about the miniature for readers?

MAVIS MACNEIL: Sure! It’s funny—I always write a program note to put in my score, but I feel like I always have to pick [just] one little slice of what a piece is about. I had a lot of fun writing “La Dame” because I really love these three instruments, specifically. I would say percussion, bass clarinet, and voice are some of my favorite instruments to write for. I think if I were asked to name my three favorites, they might be those, plus cello. So that was really exciting.

I really loved getting to write a sort of microcosm of a piece. That was a cool thing, to try to write with a time constraint, because so often I feel like I’m aiming for a longer duration.

Did the goal of composing this piece specifically to be recorded influence how you approached the writing?

MM: Yes, definitely. As I was thinking about the piece, there were things that I wanted to write that I realized wouldn’t be ideal for the approach Sputter Box was taking for this particular project, for recording separately. I tend to like to add contrapuntal and hocketing elements [in my scores], and the ensemble asked us to avoid the latter for this project. I really liked that challenge because I think it’s so easy for me to try to put [numerous] ideas into a composition and make things complex. This really forced me to focus on simplifying.

I was excited to see that “La Dame” (“The Woman”) features a text by Guillaume Apollinaire! I’m familiar with some of Poulenc’s settings of his poetry and I have a book of Apollinaire texts and translations stored away somewhere.

MM: Oh wow, cool!

Have you written for voice previously?

MM: I’ve written for the voice quite a lot. I’m a singer.

Me too! In which languages do you usually write vocal music?

MM: This might’ve been my first foreign language text, actually. I think I’ve primarily set text in English.

What was it like setting text in another language?

MM: It was fun, definitely. This spring, I joined C4 Ensemble (the Choral Composer/Conductor Collective), which is a collective in New York. It’s a really good choir. Most of the members are also composers or conductors and they’re serious singers. In hearing people talk all the time about how they think about text when they’re setting it – in terms of vowels, and especially French vowels as applicable here, passaggio, and very specific things that, as a singer, you think I would automatically be thinking of – I was more conscious of it. I was glad to have that in mind as I was approaching it.

Did you have Apollinaire’s poem in mind for this project from the start?

MM: I have a lot of books of poetry, and I usually start with text when I’m composing. My first thought was Mina Loy, a Modernist poet. She was a really interesting person. I remembered her having some really vivid imagery in short passages from longer poems. I was looking through a book of her texts – her poetry – but nothing really felt quite right. Then I noticed the Apollinaire book on my shelf.

I was reading through a bunch of poetry and I came across “La Dame.” It was the right length, I thought. It ended up being a little long for a minute-long piece, but I thought it was really cool. As I say in my program note, it’s dark, but it also has this silliness to it, because it depicts a little mouse running around, watching a corpse being carried out of this building.

I see! So would you say it conveys a level of absurdity that’s heightened, to the point where one could see it through an almost-comical lens?

MM: That’s what I thought. What happened, though, was after deciding that was the text I was going to set, I wrote it down in my manuscript-paper notebook. Then, the following week – this was in March – my partner and I decided we were going to leave New York and come to Vermont, which is where I’m from. After much deliberation, we decided that was the right choice. I brought my notebook, but I didn’t bring the book of poetry. I was kind of glad I [ultimately] didn’t have [the published translation] in front of me, because I think the English translation is under copyright, and I didn’t want to be influenced by it. It’s such a short poem—it’s pretty easy to do a literal translation of it, but I didn’t want to be looking at the other one.

What’s your vocal fach?

MM: I’m a soprano. I’ve written some songs that I’ve performed myself. I started writing the piece by going through the text and thinking about how I wanted to set that. The vocal melody came first. Alina has such beautiful, shimmering high notes. She’s amazing—it was so cool to get to write for her.

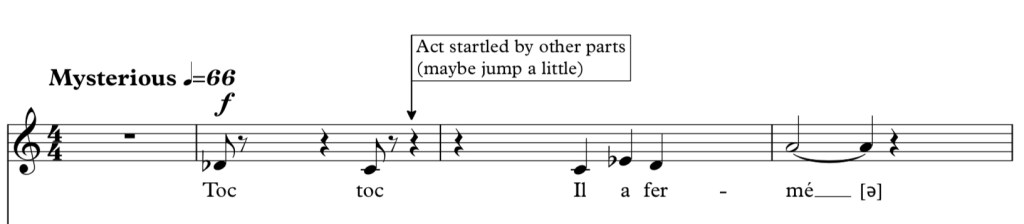

Absolutely! I see this cool indication in the score for the vocal part. It says: “Act startled by other parts (maybe jump a little).” Would you consider this marking theatrical in nature?

MM: Yeah! I was thinking about it being theatrical since I knew it would be a video performance. I think I had seen a few posted before I sent my score in to Sputter Box, so I knew they were using these tight camera shots [for their recordings] and that a facial expression would be really visible. I don’t tend to put theatrical indications in my scores, but it just seemed like a fun little thing to include.

How about extended techniques? I see there are a couple indications for bass clarinet, such as key clicks, and for djembe.

MM: Yeah! Because of the medium, I didn’t want to do anything too crazy, and the ensemble actually gave guidelines about that, so I was trying to keep it simple in that regard. I like having some different timbral things and sounds that are [somewhat] extended.

I heard this Meredith Monk interview once where she talked about when writing a piece, not letting the extended techniques be your priority or dictate how you’re writing it. I think some people do that really well and it can be fun to emphasize this one extended technique in a score. But personally, it resonated with me just to think of [extended techniques] as a bit of color to use once in a while. And that tends to be my approach.

What are some of your particular areas of interest in composing, with regard to instrumentation, style, or other aspects that come to mind?

MM: It’s shifted a lot. I think that’s true for everyone. I went to a really small liberal arts school, so I was a general music major—I didn’t get to take private composition lessons until my senior year. Even though I was trying to figure out how, it was just tricky. Since I was either the only composer at my school, or one of a couple, I didn’t really have much of a context to think about identity. Later, I went to Bowling Green State University for my Master’s, which is very avant-garde focused, so I definitely became experimental, for me. My earlier stuff was not tonal, but very harmonic. Then I played around with some more challenging sounds.

After grad school, I think the first piece I wrote was a duet for soprano and violin, which my brother and I performed. It was a setting of a passage from Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman. I incorporated some folk melodies. It was really satisfying to perform that piece, because my family liked it. [laughs] That shouldn’t really be the measuring stick, but it made me realize that I want to write music that is approachable. I don’t want to be unadventurous, but at the same time, I want to write music that the people I love will enjoy. I also think a lot about performers and who I’m working with, so that tends to drive the music that I want to write. I guess I get more adventurous or experimental if I’m writing for someone who is comfortable in that realm.

Is there anything you’d like to add that we haven’t discussed?

MM: I thought this was such a cool project. I feel like everyone has been struggling to figure out how to respond to the COVID-19 crisis, and I haven’t seen any other chamber ensembles do quite the same thing. Sputter Box also jumped on it so quickly. They have been extremely organized—they had this great idea and they took it and ran with it. It’s been a really positive experience. I feel really lucky to have gotten to be a part of it.

This interview preceded MacNeil’s second composition for the “Sputter (SHRINKS THE) Box” project. Her second miniature, “Trapped,” is a setting of a poem by Adelaide Crapsey (1878–1914). Crapsey’s poem is quite different from the narrative about the attentive mouse and its energetic movement conveyed in Apollinaire’s “La Dame.”

The poem “Trapped” instead gives the sense of an ellipsis: it’s a small capsule of fragments that expresses volumes of expansive, lingering, and hesitating phrases of time. At first read, the poetry appears to exceed its own bounds in its succinct length. MacNeil writes an instrumental texture in her score for Sputter Box that conveys that very sense of suspension in a lilting, oscillating sequence of motives for bass clarinet, punctuated with flickers of urgency in the rhythmic writing for the djembe.

Find Mavis MacNeils website at mavismacneil.com.

This article is part of a series, featuring interviews with 16 composers whose work is featured on Sputter Box’s debut album. Read the feature article here!

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity. #ShelterInSound